Deepest Hungary

Just before our weekend trip to Szeged, someone hung an old map of ‘Greater’ Hungary (1850-1870) on nearby street railings. Even a casual glance showed that a much larger nation was in existence during the nineteenth century compared to today. Hungary remained this size during the Austro-Hungarian Empire (1867-1914) until the treaty changes after World War One. I found Szeged on the wrinkled paper and decided that when this map was current, the city would have been located at the heart, or maybe in the lungs, of the former Magyar Kingdom. In Deepest Hungary. Now the country’s third largest city is located at the edge of a severed limb, close to the borders with Romania and Serbia.

Deepest Hungary is a figment of my imagination; a place so central that it should typify the spirit of the nation. If it did exist, it would probably be found in Szeged or nearby on the ‘Puszta’. Somewhere on the Great Hungarian Plain, which was once the breadbasket of the nation and then the dualist empire. Deepest Hungary would have been found at the centre of a multi-racial country of twenty million people. The Trianon treaty of 1920 took away three-quarters of Hungary’s territory and two-thirds of its population. And it didn’t get either back. Displaying the old map on the railings made this point poignantly.

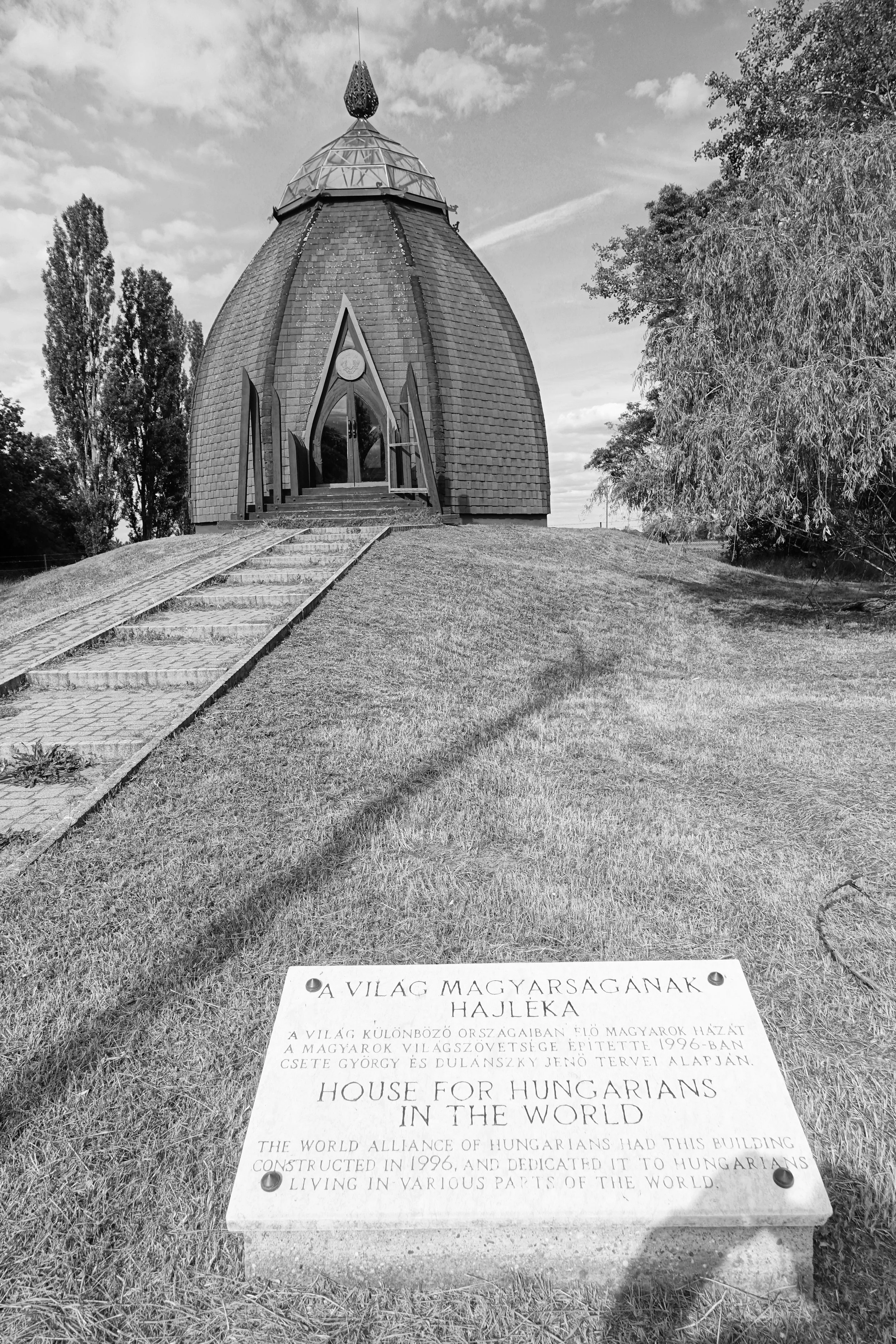

While the ‘ethnic minorities’ of the former Hungarian wing of the Empire gained land or complete independence, over three million Hungarians found themselves living in the seven neighbouring countries after 1920. Particularly so in Romania and the newly created Slovakia, and as land changed hands, significant numbers also became Serbian and Czech citizens. Estimates suggest that there are as many as two and a half million Hungarians still living in ‘Greater Hungary’. Like a scab reluctant to heal, the impact of the Trianon settlement still scars modern Hungarian politics. The map of Greater Hungary can be found on T-shirts, motorbike jackets and even mugs. An enduring symbol of disaffection

Passing through the southern Puszta on a sunny day, the affluent little towns off the M5 motorway reveal little of this lingering hurt. Places like Kiskunfélegyháza have wide, tree-lined pavements and ornate public buildings. Agriculture is still profitable in this region, with corn, tobacco and vineyards nearby. Life looks relaxed. Only government referendum posters showing sinister images of Volodymyr Zelenskyy and EU leaders, suggesting modern threats lie across the borders. The latest national referendum includes questions concerning Ukraine’s possible acceleration into the EU. Viktor Orbán, Hungary’s Prime Minister, recently placed the cost of this early accession at 49.6 billion euros to Hungary. He warns of a future when the country is flooded with cheap Ukrainian grain, emptying the Hungarian breadbasket of its lucrative loaves. A recent EU survey showed much lower levels of support in Hungary than the European average for Ukraine to join the European Union. The reason is probably much more historical than fears of cheap wheat alone.

A few miles south, the monastery at Pálosszentkút, was founded by the ‘Pallists’- Hungary’s only nativist monastic order. The holy water from the well here is supposed to have miraculous qualities, and the place has become a pilgrimage site. I found the water tasted bitter, possibly with a high iron content. It may have strengthened the soul but it wasn’t easy supping. Free of other visitors on that Friday morning, the buildings were surprisingly left open and unguarded. There was a sense of calm and peacefulness among the refurbished cloisters. Without security guards or visible CCTV, someone was keeping the site safe. Only a peculiarly modern gravestone on the adjacent burial patch and the distant hum of the M5 suggested that the twenty-first century couldn’t be left completely behind.

Grave at Pálosszentkút, burial site

In the vast attraction site, an open-air museum displays the types of buildings Hungarians probably lived in during those early days of settlement. Yurt-type dwellings were ideal for the tribes that rampaged on horseback across Europe before settling down in the mid-tenth century to form a Christian nation.

In the car park I noticed a minibus with a left-hand drive, a UK sticker and registration plate. The side doors were wide open. Curious how tourists could have discovered this remote place, I offered a tentative ‘hello’ as I stood outside. There was no reply, but as we drove away, I noticed a pair of hairy legs with sock-clad feet moving about inside. Brits get everywhere, even if they aren’t always feeling sociable!

Ópusztaszer open-air museum building.

One of Szeged’s many market squares.

On the Friday evening, we ate at a riverside fish restaurant just outside the city centre. Many local houses are built on stilts, as the Tisza still floods the low-lying suburbs occasionally. I enjoyed grilled carp, not a fish I normally favour, but this one tasted as fresh as if it had been swimming only hours earlier. Szeged is famous for robust fish soups (halászlé) and tripe stew. Its cakes are renowned as the best in the country. The restaurant was surprisingly quiet considering the excellence of the food. This may be explained by people attending the Majális events around the City. These make up the traditional Hungarian spring festival celebrated across the country.

After dark, Szeged really comes alive during the celebratory May days. We attended the biggest wine festival I have ever seen, with bottles on sale from cellars everywhere in Hungary. Live music blasted out from a central stage, and the aroma of sausages and kebabs taunted the taste buds. At our table, a group of Szeged University IT graduates from the early 1980s used the event as an opportunity for a class reunion. Dispersed across the country now, they generally seemed to have enjoyed successful careers. Nostalgia lingered in the air for carefree student days on this balmy night in the playful city.

Albert Einstein departing the Academy of Science Building in Szeged making haste towards the wine festival.

Statues at Ópusztaszer depicting the original seven Hungarian tribes.

Poster publicising the 2025 national referendum.

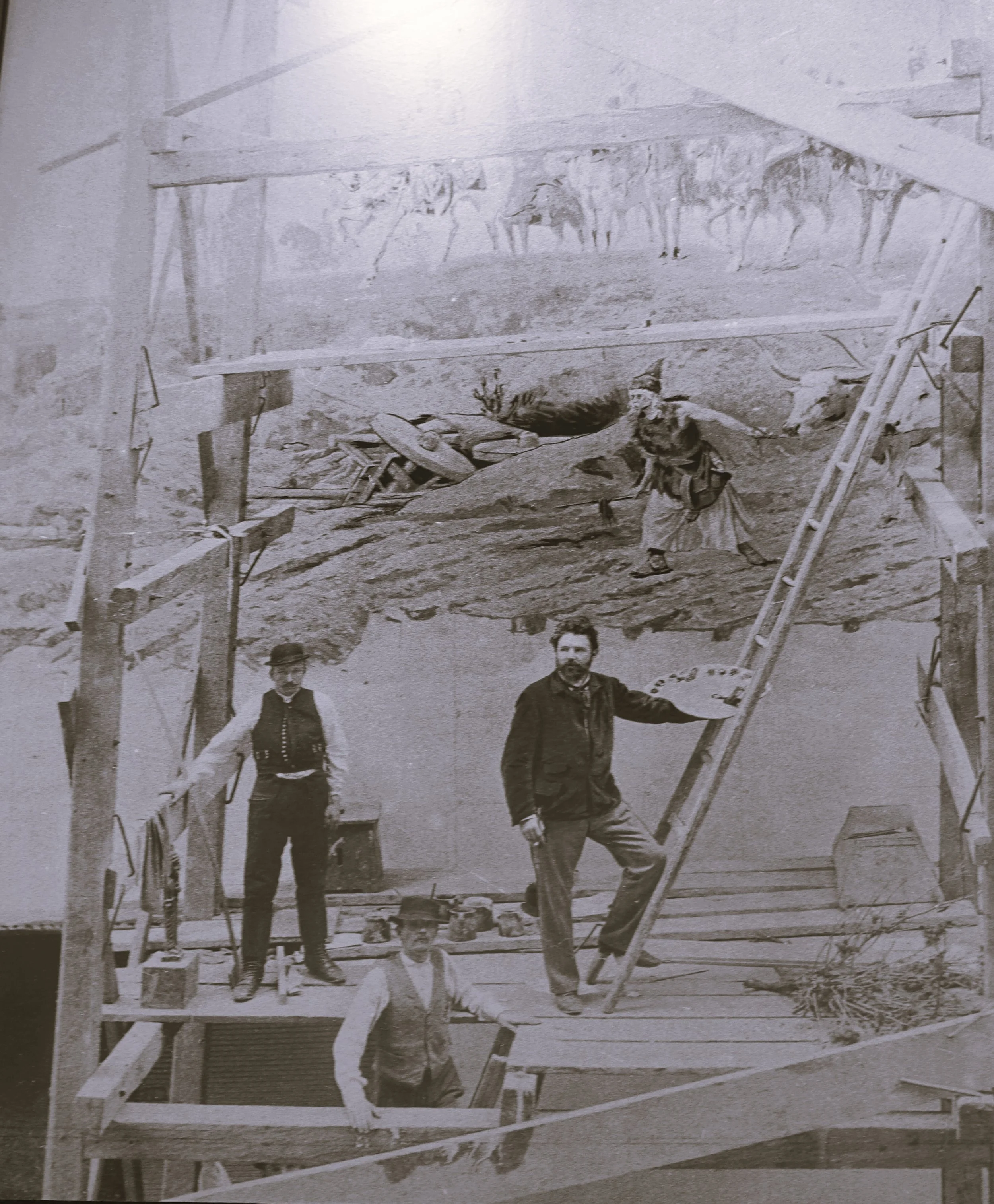

The Puszta south of here remains flat and featureless. The remote site of the Ópusztaszer Heritage Park pays homage to the founding of the nation. Models of the seven tribal chieftains reputed to have entered the Carpathian basin, bringing Magyar culture to Europe in 895 AD, are located on a small hill. Inside a modern rotunda nearby, the fantastic Feszty panoramic painting entitled The Arrival of the Hungarians is stretched around the walls. Created between 1892 and 1894 by a team of notable local artists, it was originally displayed in the City Park in Budapest. The arrival of the battling tribes through a Carpathian valley at Munkacs near the modern Ukrainian border was portrayed in oil on a canvas measuring 15 metres high and 120 metres wide. It can now be seen in its renovated form at the Heritage Park, and the accompanying sound and light show is dramatic and enticing. Exactly where the Hungarians came from is the subject of much study and speculation. Linguistic and other evidence suggests that their origins lie somewhere in Central Asia.

Section of the Feszty panoramic painting- The Arrival of the Hungarians- picture showing original artists at work in Budapest.

South to Szeged, the road runs parallel to the mighty Tisza River. A major waterway that meanders through the Great Plains. Its source lies in the Subcarpathian highlands, now modern-day Ukraine, but it was a region influenced or ruled by Hungary from 895 until presented to Czechoslovakia after the Trianon settlement of 1920. Its symbolism is such that the rising star of Hungarian politics, Péter Magyar, attached himself to the regional conservative Tisza party, and together they offer a serious challenge to Viktor Orbán’s hold on power, which will be tested in a general election by April 2026.

Szeged is a pleasant and affluent city near the confluence of the Tisza and Maros rivers. The Tisza flooded badly in 1879, and Szeged received help from all around the world to create flood barriers and a new city befitting Hungary’s sharing of power with their former Habsburg rulers from Austria. It is a city of wide, tree-lined avenues, palaces and beautiful squares, with an almost Mediterranean atmosphere. While it’s easy to get roasted by the summer sun on the nearby Puszta, the walking streets of Szeged are protected by huge sun covers. Exceptional Art Nouveau buildings were built during the twentieth century, and Szeged University laces the city with many buildings and a vast student population. It boasts Nobel Prize-winning alumni such as Albert Szent-György, discoverer of vitamin C in 1912. More recently, Katalin Karikó was one of the two key developers of the mRNA vaccines used against COVID-19 and was awarded the same prize in 2023.

Secessionist (Art Nouveau) building in Szeged City centre

Over several glasses of red wine, one ‘informatikus’, Sándor, was enthusiastic to tell me how he had worked out mathematically that Shakespeare’s writings were actually the work of the Earl of Oxford. An old idea with new evidence to support it. Oxford was not an obvious candidate, as he was supposed to have died before Shakespeare’s final works were completed. Sándor has found mathematical evidence involving the number 137 to prove his point. This he didn’t elaborate on but has lectured about at renowned mathematical institutions. He also said that there are written clues in the sonnets and Ben Johnson’s correspondence, which suggest that the Earl survived after his recorded date of death and could indeed have been the author of the twelve plays written after 1604. In this version of history, Shakespeare was merely a drunken actor. It was an unexpected conversation to have in Deepest Hungary, but Sándor has made this topic his speciality, liaising with academics in Oxford and Reading, as well as actor Sir Derek Jacobi. And who am I, with my dodgy mathematical skills and sketchy knowledge of all things Shakespearean, to say that he’s wrong? Especially after a few glasses of robust red wine.

The city is packed late into the night with revellers, and looking towards the Tisza, I see a girl on an electric scooter whiz along the bankside path. Her mane of hair was blown back by the river breeze along with a stream of balloons, shining under the waterfront lights. A happy rider heading off into the night, to a party perhaps, she was celebrating her birthday in style. Szeged is an optimistic city to be a young person in. Come to think of it, it’s not a bad one to be an oldie either!

Back in Budapest, the tattered map was no longer suspended from the railings. More likely, it is to be found hanging on a new owner’s wall, in lament for the past, rather than consigned to the rubbish bin of history. Not only in Deepest Hungary does Trianon’s legacy die hard.

Sources

Hungarian Human Rights Foundation

Hungary Today

Wikipedia